Typically, the process of learning a new Romance language as an English speaker can be expedited by simply taking advantage of congruous character sets and/or character phonetics in that language. Both French and Spanish use the same/slightly augmented alphabets respectively, and carry varying degrees of phonetic similarity in each character. This does not trivialize that process at all, since learning said languages can still be several year-long endeavors, but I think most English pupils will recognize this fact and leverage the alphabet when practicing reading and writing, and the phonetics when speaking. But for non-Romance languages, such advantage in studies is not present. The character sets often encompass thousands of characters and have little/no reliable phonetic clue behind each of them. Enter the Chinese character set used throughout the eastern world, known as “hanzi” or “kanji” or just 漢字.

As someone who has studied these characters, it never ceases to amaze me how the more I come to understand each character, the less certain I am about the dimensions of size and complexity of the character set as a whole. Learning the phonetic scripts of Japanese (hiragana and katakana, 46 characters in total) are no doubt trivial compared to the obstacle of 2136 Jouyou kanji (常用漢字) that constitute the “normal use kanji.” Even after learning that many, you might as well pile on another several hundred or so of these chicken scratch scripts so you can understand proper nouns and outlying common use words when reading NHK articles – a litmus test for any student in this language. The real, final figure on the number of required kanji for passing such tests may be greater, say ~3000 as a rough estimate. Each of these characters can be quite difficult to either write or read, sometimes having many strokes, and sometimes a plethora of ways to read/speak them.

読

(read)

- Onyomi (音読み, mainland, sinitic readings):

- toku, doku, tō

- Kunyomi (訓読み, island, Japanese readings):

- yomu, yomi

To satisfy the need for more elegant methods for study, a variety of different isolated kanji study resources have been published. Many of these explore different approaches than just dictation and reference, such as mnemonics, sample vocabulary, English keyword association, and an order of introducing the characters; this will be touched on as I compare these works. I will take a somewhat well-known book that is considered a staple for students, Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji, and compare it against a piece I feel is overlooked, Conning’s Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course.

Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji, The Household Name among Students

Colloquially known by the acronym “RTK,” in English internet circles, this book has been the go-to suggestion for isolated Kanji study for many students. Published in 1977 by James W. Heisig, it has managed to continue to be relevant for quite some time. This is astonishing to me, since Heisig writes that he came to Japan without a iota of understanding of the language, yet during his time devoting himself completely to the language, he managed to collate all of his recently acquired understanding, study notes, and produced a study resource that has the notoriety that it has today. No doubt the man was being approached by all of his fellow students during his classes, asking for copies of his notes, not dissimilar to the scenario in any high school class where the sole student that does take notes shares said knowledge with all people in said class, all of whom seem to be unable to muster enough strength to bring pencil to paper. Indubitably, one would have to be rather serious about learning the language if a man such as Heisig had the ultimate goal of exploring Japanese philosophy. The work itself speaks to that effect, that of a labor done out of necessity, one done from a man looking to learn these characters in an efficient and systematic way, but not a linguistic or etymological one; Heisig says just as much in the introduction. Perhaps that it is why this book has stood the test of time and has the fame that it does.

Heisig’s Process

It is important to note that the mission statement of RTK is the following:

The aim of this book is to provide the student of Japanese with a simple method for correlating the writing and the meaning of Japanese characters in such a way as to make them both easy to remember.

James W. Heisig – Remembering the Kanji

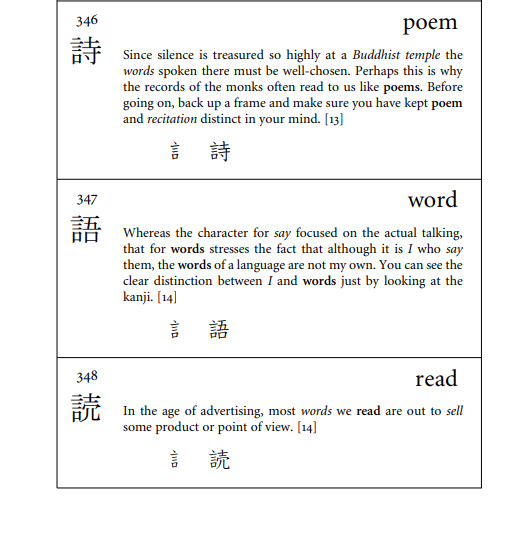

The material provides nothing in terms of vocabulary, ways of reading the characters, pronunciation. The mission here is to encapsulate a every character with a single English keyword, tied together with a single one of Heisig’s “stories.” These stories are ultimately mnemonic devices that paint pictures with one’s imagination, prompting recollection of that character’s meaning and writing with a colorful, sometimes grotesque tale. This is done for The picture below is an example of the character 読 and its accompanying story.

This character has a few constituents, namely 言 (words) and 売 (sell), which are are also composed of more basic radicals/primitives/kanji 口(mouth) and 士(gentleman, samurai) among others that help form the story for this character from their own individual stories:

言

“Of all the things we can do with our mouths, speech is the one

that requires the greatest distinctness and clarity. Hence the

kanji for say has four little sound-waves, indicating the complexity of the achievement.”

売

“A samurai, out of a job, is going door-to-door selling little

windup crowns with human legs that run around on the µoor

looking like headless monarchs.”

士

“The shape of this kanji, slightly differing from that for soil by

virtue of its shorter stroke, hints at a broad-shouldered,

slender-waisted warrior standing at attention. When feudalism

collapsed, these warriors became Japan’s gentlemen.”

口

“Like several of the first characters we shall learn, the kanji for

mouth is a clear pictograph. Since there are no circular shapes

in the kanji, the square must be used to depict the circle.”

…

The early characters for “mouth” and “gentleman” are usually primitives/radicals that come earlier in RTK, so when you come across a more complex character like “read,” you have a collage of different stories creating an imaginative lattice that acts as a mnemonic for remembering the significance and method of writing the character.

This is done for 2200 characters. The common use Jouyou kanji are included in this material (interesting to note that some earlier editions of this book came about before the Japanese Ministry of Education defined more common use kanji. Back when Heisig first published, Jouyou kanji numbered 1945). Some of these are primitives and radicals, and are not seen alone, but compose kanji. Heisig states he was careful to include the ones needed to compose his stories.

Conning’s Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course, An Overlooked Alternative

I first came across this material after reading a rather scathing piece that considered isolated kanji study to be inefficient compared to vocabulary study and osmosis. This cynical sort wrote that if one were to pursue isolated kanji study against his suggestion, then Kodansha’s Kanji Learner’s Course would be a must-buy.

First published in 2013 by Harvard graduate Andrew Scott Conning, it provides a method not exactly novel to the world of isolated kanji study, but a professional, comprehensive evolution of similar albeit slightly altered methods explored by Heisig in RTK.

Conning’s Process

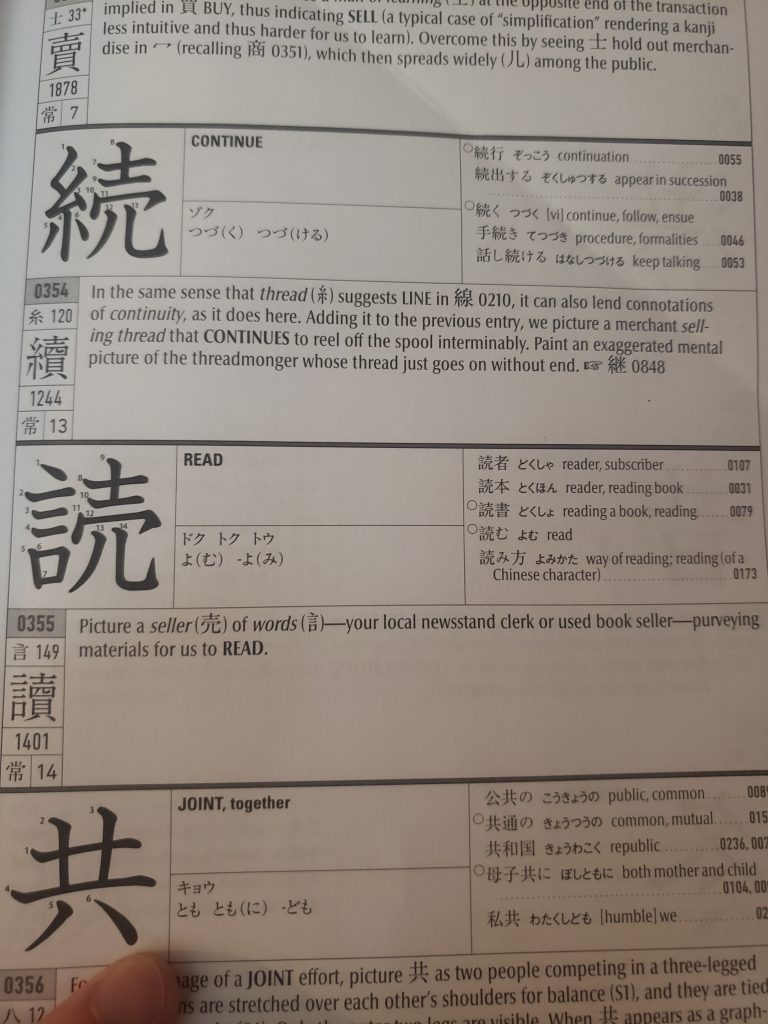

Like RTK, Conning uses stories as mnemonic devices to aid students in recollection of kanji, but with a focus on the different ways of reading the kanji, as well as contrast in characters that share identical structure. Compare this mission statement with that of RTK’s:

The primary goal of this course is to help you learn and remember the basic meanings of each kanji. It is also designed to familiarize you with the principal pronunciations of each kanji as you learn its core meaning(s), and to actively apply both the meanings and the pronunciations in learning a few sample vocabulary words.”

Andrew Scott Conning – Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course

The excerpt of the entry for 読 above shows how much information is presented compared to that of the one for RTK. Not only do we have a story, but also all the possible ways to read that character, a small vocabulary section, stroke orders, the base radical, and even prewar versions of the character that have long been obsolete. One of the bigger differences between RTK and this book is the order in which the characters are presented. Heisig went by a radical/primitive/theme order that seemed rather arbitrary, and often devoted many entries to graphemes that do not stand alone as kanji. This book presents the characters on a frequency of use basis within Jouyou set, where the order is not exactly strictly radical after radical, but builds upon itself cumulatively with the vocabulary to the left. You will never find a Chinese compound in the left hand side that has not been introduced earlier in the book! The material points out with a small pointing hand icon at the end of the story to similar kanji that often are confused for the one you are currently studying.

This book teaches 2300 characters, includes proper noun name kanji 人名用漢字 or jinmeiyou, which reside outside of the standard use set, but nonetheless are integral.

A Comparison – Which Piece of Literature is More Efficient?

After reading the entirety of RTK, and about a quarter of KKLC, I can say with some authority that I might be a good judge for determining which of these study materials is better. In all fairness, both books accomplish what they set out to do (RTK’s scope is stated to be as much when reading the introduction), but often a student’s ultimate goal is to be able to read and speak the language. I think RTK is recommended a bit too much because of this, since it supplies no ways of reading the individual characters, one cannot speak anything after reading RTK, and can only form a vague idea of what a sentence is talking about, granted they know enough grammar. Because of this, I recommend KKLC over RTK.

Leave a Reply